The deeper, and deeper I go into my understanding of innovation, and what it actually means for the...

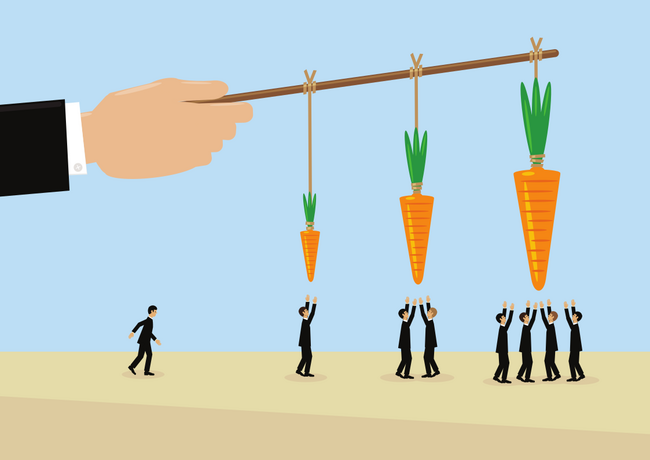

Innovation, and the challenge of misaligned incentives in the real estate industry

“What Incentive do they have to take a risk to do something different” so said Head of Technology Strategy & Digital Management at QIC Real Estate, Nikki Greenberg in my interview with her a few weeks back.

This reminded me of a quote I had seen in a Forbes piece a while back. I dug it out.

Henry Doss aptly pointed out that “when reward systems conflict with vision, the reward is most likely going to carry the day” and that the “greatest enemy of innovation may be an ill-advised reverence for the status quo. And nothing fuels organisational status quote more insipidly than entrenched, unchallenged, long-standing incentive systems”.

Powerful points.

It struck a chord about something I had heard a few times. Companies struggle with their digital transformation journey, in part because of a misalignment of incentives as they look to evolve.

Transformative individuals need transformational incentives.

Treating them the same as everyone else will cause you to fail at the first hurdle. Not realising that their entire role needs to be viewed differently from everyone else will be a huge mistake in your leadership.

- Innovation strategies will be risky.

- Innovation strategies are long-term in view

- Innovation strategies will often be carried out by relatively new hires/roles

- Innovation strategies often compromise core business models

- Innovation strategies are often compiled by a team, not single individuals

- Innovation strategies are more creative than structured

- Innovative strategies will be constantly testing and iterating

Leaders who view innovation as an extension of traditional, linear style management techniques, with incentive initiatives aligned, will struggle to bring about real change, and may, despite having the correct vision, may hamper its correct implementation. In turn, they may be no more successful than those with no vision, and the business stagnates regardless.

Conflicts while implementing a transformation agenda, highlight some of the challenges of incentive setting. You have to balance this all out for true alignment enabling teams to comprise, not compete.

Examples of conflict may include:

- CEO vs. Innovator

- Legacy teams vs. Innovation teams

- Shareholders vs. CEO and or Innovator

- Employees vs. Innovator

- Customers vs. Innovator

Why even bother going on the journey of innovation?

There has never been a greater time of flux in financial markets as CEOs battle to keep businesses relevant, and source continued growth.

Technological change often ranks as one of the key drivers of CEO motivation. In a 2016 KPMG survey of 400 CEOs based in the US, keeping up with new technologies and responding as new competitors overturn business models ranked as the two top concerns, cited by 81%, and 76% respectively. In a 2017 PWC poll over nearly 1,400 CEOs from 79 countries, respondents said innovation was the aspect of their business they most wanted to strengthen.

It is this desire to strengthen, that makes the discussion around misaligned incentives even more prescient. In a recent McKinsey report, they stated that ‘companies who implemented financial incentives tied directly to transformation outcomes achieved almost a fivefold increase in total shareholder returns (TSR) compared with companies without similar programs’

Despite this, they also stated that their ‘research found only 2/3s of companies adopt a financial incentive program when embarking on a transformation.

We will discover later that financial incentives are not the focus of strategies but are still prescient.

The challenge of misaligned incentives, and an introduction to the one-armed bandit problem

Perhaps the largest challenge business leaders (and shareholders) face is that of picking the road less travelled. In traditional real estate businesses, returns are (generally) known. They are repeatable, consistent and predictable. This generally means a happy management team, and explains a shareholder perspective of value investing who likes to see the stability and known returns.

Challenging the status quo is not straightforward. It threatens normality in the short term with no promises of success. This creates a different management mentality and likely a more nervous shareholder base.

A 1952 report by the mathematician and statistician Herbert Robins goes some way to explaining this. It became known as the multi-armed bandit problem as the implication was that the learnings of probability distribution and reinforcement learning could be applied to the one-armed bandits in casinos.

Simply put, it really centres around ‘Exploitation vs. Exploration’. The choice is to stick with what is known and continue (Exploitation) or spread resources and test (Exploration). In the casino example, upon watching people play a row of ‘one armed bandits’ do you stick with the one you saw that pays out regularly, or do you spread your money across a bunch of others, in the hope of finding different, and larger profits’.

There is a perennial tension there between the two competing dynamics. As Gustavo Manso puts it in his research paper for Berkeley University entitled ‘Creating Incentives for Innovation’, ‘Exploration uncovers information about potentially superior methods, but frequently leads down blind alleys, wasting time and effort. Exploitation relies on proven techniques that have high probabilities of reasonable payoff, but inhibit discovery of superior methods’.

Considering what we have learned about the bandit problem, let’s review some of these incentive challenges:

Productivity Challenges;

This speaks to culture, having all staff aligned and bringing about an attitude of flexibility and testing. Imagine, however, that they are not, and you haven’t addressed the issue of culture. You have teams working in silos, each particularly protective of their area. Not wanting to be blamed if it goes wrong

Legacy teams maintain the ‘status quo’ to use Henry’s quote from earlier in this article. Regardless of their transformation project, your innovation teams will likely require input from legacy teams to test what is in existence already. This is likely to cause a productivity issue around conflicting motivation and responsibilities.

To quote Nick Tune in Medium, ‘For stream-aligned teams to build quality products and business capabilities at pace, high levels of cooperation within the organization are required. Teams need the ability to develop, test, deploy, and operate software but they can only do this within the constraints imposed by operations, security, and some other teams. This is where misaligned incentives can decimate productivity.

When operations teams are only measured by how well production environments are running, and security teams are only measured by how secure things are, these problems are always going to exist.”

Innovators will cause huge conflict here unless everyone shares in the success, and supports the failures

The solution is to tweak the incentives. I will come back to that in a later piece.

Delivery bottlenecks

Productivity is hurt when there is no collaborative culture of testing and iteration. A similar issue occurs when dealing with the prioritisation of delivery in an organisation as well.

Innovation teams will want to test continually. This will put demands and stresses on existing legacy teams who may be needed to implement some of the tests. Consider a digital team wanting to make continual tweaks to a website (to give a most basic innovation example), but it needs the dev team to do the updates. If a dev team has to support requests from everyone else as well, who and how do they prioritise? The dev team is likely to have their own priorities, which are pinned to their own incentive scheme upon which they will be judged.

They will not be in a hurry to risk their own incentive structure

The rise of Individualism

There has long been a tradition of personalised targets and incentives. SMART goals are known by almost everyone but when you break them all down they are super difficult to apply in an innovation incentive scenario.

- Specific (simple, sensible, significant).

- Measurable (meaningful, motivating).

- Achievable (agreed, attainable).

- Relevant (reasonable, realistic and resourced, results-based).

- Time-bound (time-based, time-limited, time/cost limited, timely, time-sensitive).

When you consider SMART goals they are almost impossible to relate to innovation goals which are much more collaborative and team-focused.

SMART goals are very much a 1:2:1 agreement on targets and give people a very personal list of objectives to complete to reward individual performance.

Innovation is not Specific. It is broad.

Innovation is not generally measurable and therefore tough to set Achievable targets either.

Henry Doss who I have referenced previously talks about the importance of ‘soft values’ which are ‘fuzzier’ and ‘more difficult to measure and more difficult to define’

Therefore, the very nature of innovation of being broad, creative, constantly changing, team-based, and long term in focus means these sorts of goal and incentive setting is in error.

Focusing on short-term delivery, not continuous and gradual improvement

Incentives schemes are tricky. As a result, it is often easier to focus on short-term incentives that are based on actual delivery. Quantitative results, time spent on a project and binary outcomes. Did it work, did you succeed or did people benefit from your actions?

Innovation has to be viewed completely differently. It is all about constant and gradual improvement. People will fail. They will not want to fail. They won’t set out to fail, but if they are instigating change, it is inevitable. It should be viewed as ‘short-term progression which brings about a continual and gradual improvement because in the failure there are learnings that can be viewed as improvements in and of themselves.

Short-term financial incentives are not the answer

With all of that said above, this quote from Gustavo Manso is particularly important to consider.

“Innovation requires the exploration of new, untested approaches that may very well fail, which flies in the face of the incentives that typically guide business behaviour.” He goes on to say “Standard pay-for-performance schemes that reward short-term financial results and punish failure with low compensation and possible termination may deter managers from trying new things in favour of tried-and-true methods that offer predictable outcomes”

This speaks to something that I am thinking a lot about; the culture at the heart of innovation and change.

Whilst financial incentives are undoubtedly welcome, they should not shape either the long or short-term mentality of innovation. It goes deeper than that, and it speaks to the point Gustavo makes, which it is as likely to succeed as to fail, and perhaps speaks more about teaching the entire organisation that it is okay to attempt new things and not always succeed, but to learn.

His research at Berkely found that “in the context of executive compensation, the economic analysis indicates that the optimal innovation-motivating incentive scheme uses a combination of stock options with long vesting periods, option repricing, golden parachutes, and managerial entrenchment. With these provisions, compensation depends not only on total performance but also on the path of performance. A manager who oversees a successful program of innovation may perform poorly at first but do well later, earning more than a conservative manager who does well initially but poorly later. Moreover, boards may be tempted to dismiss the innovating manager because of poor early results, but entrenchment provides the time needed to allow new methods to bear fruit.”

That last point there speaks to one of my initial statements about the conflicts that might be present. The culture change has to be throughout the organisation.

The politics of incentive structures

Continuing this narrative on conflicts present in organisations, it is important to highlight why this presents a problem. This ‘conflict’ is even more evident because you will likely have contradictory incentive schemes prevalent throughout.

To quote Nick Tune; “On one hand people and teams need to collaborate to deliver capabilities and products. Yet on the other hand the organization chart is a competition. It’s very easy for individual competition to overpower the need for collaboration and become highly political, especially higher up the org chart”

Quite often, with innovation teams being brought in you will create a competing force. For example, you may have an existing technology leader, which is then put under the spotlight with a new digital leader asking questions of their role. Both would likely be vying for the top job to cement their role in the future organisation, and this is going to be difficult not only to create a culture of collaboration (they will need each other in the short term), but also when it comes to reward. It wouldn’t be a surprise to see “leaders purposely making harmful choices to the company in order to lock in their personal status” as Nick puts it in his Medium article

Taking it to perhaps a more serious level is the clash of material interests in a firm. A CEO and a broader business responsibility is to provide a return to investors and shareholders. Therefore CEOs and other significant shareholders have a huge political conflict with shareholders.

“Heightened board pressure may be encouraging managers to exploit already successful areas of expertise at the expense of riskier avenues of exploration” states Manso in his Berkely paper. He adds, “A large legal industry is devoted to seeking out instances in which it can be argued that managers acted in their personal best interests at the expense of shareholders. Undoubtedly, this legal liability disciplines managers by raising the costs of negligence and self-dealing. At the same time though, theory suggests that fear of shareholder litigation could stifle innovation. Managers may have strong motives to reduce their legal exposure, which could feed short-term thinking and risk aversion”

The politics and legal ramifications of a misaligned company structure is hugely problematic for an organisation or company that is looking to truly innovate. It also brings reference to instances of the challenges of the Innovators Dilemma, a seminal theory, and book by Clayton Christensen. How can truly groundbreaking companies, keep innovating while not breaking some of what made them truly special in the first place.

We have written about this previously with specific reference to the property industry. In this case, it was about a truly revolutionary property portal business in the UK that is just not able to evolve; Rightmove and the Innovators Dilemma.

Incentives are being built around what you already know how to measure

As discussed already, incentive schemes are traditionally tough to set up and get correct. There is no surprise you have remuneration committees that diligently work through what makes for a correct incentive structure and compensation.

Often comfort is drawn by what is already known in order to set the correct incentive. This is generally a known known, in the indicator of the incentive being hit. Companies know what they are trying to do. Often it will be a financial marker or something that can be ‘measured’, that is both reliable and predictable.

The misalignment is likely to come if a plan is built around measures that preceded the incentive. If it is a pre-existing measure, you are likely not in possession of the best indicator for an incentive plan.

Incentives being too focused on hierarchical goals

Referencing Henry Doss’ excellent piece in Forbes entitled ‘Five Ways Incentives kill Innovation’, written back in 2013, he puts this challenge excellently:

“As a rule, most incentive plans align to a stacked set of goals that follow organisational structures. While on the surface this seems to aid in aligning everyone toward the same goals (it does) there is also an intrinsic challenge in this structure.

In a reward "chain" incentives become increasingly dependent on adherence to a normative set of behaviours, the further up the chain you go. This can mean that the higher you go in the organization, the more myopic the focus can become on compliance with the norm. When this happens, risk, disruption and failure become highly negative values, and the possibility of innovative behaviour diminishes”

–

Often it is quoted that a true digital transformation journey can take 7-10 years. When I first started on my journey of research into this particularly interesting area of business, I just couldn’t understand why something so simple, could take so long.

The very notion of this being more of a mentality shift, than a technology shift, hit me quickly. I started to realise it wasn’t as straightforward as I had thought. Adding to that the concept of how people were incentivised added to that realisation.

Even before the true journey starts, you have to address the culture of your organisation to factor something into the journey that is so basically simple as how do you incentivise people to carry out the actions that is in the interests of the company in the long term but may cause undue stress on the business, the staff, customers and bottom line in the short term, is a fascinating challenge for any leader.

In coming thought pieces, I will look to bring in a greater understanding of how to solve these issues by instilling the correct innovation incentives.

Further reading:

Misaligned Incentives Fuel Organizational Dysfunctions

15 Ideas for Rewarding Innovation in the Workplace

KPIs and Employee Incentives to Encourage Corporate Innovation | Collective Campus

KPIs and Employee Incentives to Encourage Corporate Innovation | Collective Campus

Four Ways Incentives Promote Innovation

Four Ways Incentives Promote Innovation

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/35074763.pdf

Five Ways Incentives Kill Innovation

Five Ways Incentives Kill Innovation

http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/manso/cii.pdf

The powerful role financial incentives can play in a transformation